Jerry Lewis – a personal tribute

Jim Schembri reflects on what it was like being allowed to get so close to the comedy great.

Given the formidable heft of his legend, it was quite a relief to take my seat opposite Jerry Lewis – one of the 20th century’s defining icons of comedy – and reduce him to tears.

Visiting Melbourne in 2008 to raise money for muscular dystrophy – a cause that had long overtaken comedy as Jerry’s central concern in life – I knew the prospect of interviewing him in person would bring on a case of bladder-testing nerves. I needed a gimmick to break the ice.

So, using a portable DVD player, I got Jerry to watch himself in the famous audition scene from his 1958 film Rock-a-Bye Baby. He loved it, and it was a singular thrill watching Jerry heartily laugh at himself. It was a cheap ploy, sure, but it worked.

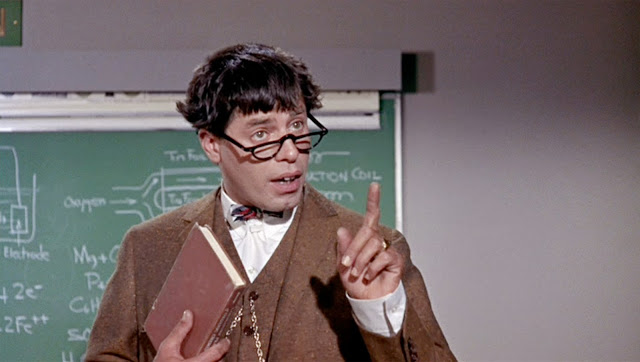

Relaxed and relieved, I then quizzed him about his life and career, speaking slowly and loudly to overcome his hearing loss. I asked about his partnership with Dean Martin; his good films; his bad films; his milestone movie The Nutty Professor; how, by the time he was 40, Jerry had popularity and power unmatched by any comedian in history, before or since.

What was supposed to be a tight 10-minute chat stretched into half an hour. He said he’d not only enjoyed the interview but that it was – and I quote – the best interview he’d ever had. As monstrous an overstatement as this obviously was, it still floored me.

As I was lead outside by a member of his entourage they told me that we had “clicked” – something, I was assured, that didn’t happen often – and that Jerry wanted to see me again.

He was true to his word. For the rest of his time in Melbourne and during his subsequent visit in 2010 Jerry made me part of his inner circle, keeping me close, usually within arm’s reach and often insisting on my sitting next to him at major events.

Though a frail figure in need of a wheelchair, Jerry liked walking when he could, even if it meant only a short distance across a road, through a foyer or to a limo.

This required somebody taking his arm for support, and often it was mine. Initially he would ask for it but time came when he would simply gesture to me and I would offer him my elbow to grab. As often as it happened this unspoken intimacy was impossible to get used to.

He had assistants and a manager, but Jerry ran his own roost, was across every detail of his schedule. Who am I meeting? Where are they from? What have they done?

Watching him meet fans, I really came to understand the meaning of “awesome”. He was that, and you could see it in the stunned expression of people who had grown up with his films, and who were now bringing their children up on them. They would grin nervously as they posed for photos. (Real cameras only. Jerry hated phone cameras.)

And when Jerry summoned you there were no excuses. The rule was simple: he calls, you come.

Jerry’s people called – as they said they would – about having dinner one night. Great, but it was that night. I was in Melbourne, he was in Sydney. Not an issue. I was to meet him at his hotel, no question. So I did, thankful there was a flight that would get me there in time.

In a cordoned off corner of a secluded Italian restaurant we dined, Jerry at the head of a long table lined with his crew. I sat to his right, opposite Sam, his wife and the love of his life, whose hand he held at every possible moment.

It’s at rare moments like this your brain goes numb with euphoria. This is as close to Heaven as a journalist gets – and Jerry knew it. He was giving me what he knew I wanted.

So, sitting there next to a personal hero whose work I adored and knew intimately, and with no time limit, I drilled him with every question I’d ever wanted to ask – and he obligingly answered with as much detail as I could stand.

Some remarks were on the record, such as his pioneering of video assist technology on his 1963 classic The Bellboy, a device that allows a director to immediately review footage (now a standard part of any movie set). Some comments were not for publication, such as what he wanted to do to people who violated his copyright, especially online.

We spoke of his high output and tireless work ethic, a trait he shared with other entertainers of his generation. While making The Bellboy at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami – writing, directing, producing – Jerry was also performing two packed-out shows per night.

Jerry was always bemused at people’s fascination with this. To him, and to his fellow entertainers, working hard was considered affirmation of ambition. It meant you were wanted, and being wanted was what life was about, especially for a comedian, who needs a room. Why the fuss?, he would say.

At that time in the 1960s, Jerry was the hottest thing on the Paramount lot – and he wasn’t even 40. When it came to discussing his movies with the suits it was always a matter of when best to release his films, never whether anyone would come.

As Jerry scooped into his pasta he remembered the era clearly, driving around the studio in his golf cart, running open sets – people were actually allowed to come and watch him film – and making sure the brass didn’t mess with his routine.

Even at the end of the evening, when I thought I’d exhausted every question I had in my head, he asked me to let him know if there was anything else I wanted to know. “Just call me direct. You’ve got my number.”

Dropping him off at his hotel, I went to get out of the limo to call a cab. No dice, Jerry commanded as he ordered his limo driver to take me back to my hotel across town.

The memory of that ride gliding through the empty streets of late-night Sydney still feel surreal. There I was sitting in the back of a limo on Jerry Lewis’s dime.

Although he never allowed it to enter his work, Jerry was an accomplished vulgarian. He didn’t swear much, but when he did he made it count, either to make a point about efficiency or punctuality – you didn’t dare be late for a meeting with Jerry – or to get a laugh.

During conversation, he had a habit of breaking into a sentence by asking whether your brain was OK, a query embellished with a few choice F-bombs. I once said I was worried about imposing on his time. He told me that if I felt that way I could go f*** myself. Somehow he made the words sound warm.

Many of the tributes since Jerry’s death have made mention of what a grump he was. Sadly, for better or worse, the reputation he earned in his latter years as a curmudgeon is at least partly true.

Jerry did not suffer fools. He was fully aware he could be short-tempered with people who didn’t measure up. He hated incompetence in the workplace with a passion, his argument being that an incompetent crew member meant that somewhere was an competent person who was unemployed.

He had spent his life holding himself to a very high standard and now expected the same from everybody else. Sure he could be grumpy, he would say. But he was entitled.

Just how unforgiving Jerry could be came to pass at an annual breakfast gathering of Melbourne secretaries – an event that had been rescheduled by weeks to accommodate his appearance.

A few minutes into his presentation a technical glitch shut down the projector of his slideshow. Without ceremony he walked off. People expected him to return, but he didn’t. It was a disaster. One of the event organisers was reduced to tears.

This surliness was far more pronounced on his 2010 visit to Melbourne. Jerry had begun taking some of his supporters for granted, and it was painful to observe.

In one particularly sour encounter Jerry was presented with a large cheque. The fundraisers waited anxiously in a conference room, but when Jerry finally ambled through the door he was perfunctory to the point of insult. He did his greetings and posed for photos as though it was he who was doing them the favour, then shuffled out as though disappointed they didn’t have more to give.

It was tough to imagine the disappointment of that, of going through all the anticipation of finally meeting a legend of comedy, only to come away feeling less special than before he walked into the room.

Still, having witnessed with a wince the blunt edge of his manners Jerry never treated me with any sense of dismissal or disrespect.

Yes, he would spend an early-morning coffee going over something I had written about him in that day’s paper, pulling it apart word by word, asking why I wrote this and what I meant by that, but he took my responses with good humour.

And he never got short with his crew. His curtness was reserved for those on the other side of the door.

It’s still hard to describe what a privilege it was to enjoy such proximity to Jerry Lewis. He said several times that it wasn’t because of an implicit promise of good press that he warmed to me. He trusted me. There were a select few journalists he connected with in a similar way, he said, and he considered them friends.

Jerry would send me articles and books in the mail, occasionally a photo. To get a casual phone message from him saying he was coming to town and was looking forward to hanging out for a few days is still difficult to absorb.

And Jerry was funny. He wasn’t on all the time, but when he was he had the impish energy of a monkey, a term he often used to describe his younger self when he and Dean Martin were America’s #1 club act, with Dean the debonair straight man while Jerry jumped across tables, slapping expensive steaks into people’s faces.

There was something in Jerry’s DNA that always kept part of his brain tuned in and on the lookout for jokes. He was constantly in search of another gag, a new pun, a play on words.

Anything would do. He’d do knock knock jokes. Sometimes he’d hear a sentence, then work backwards to create a set-up that turned it into a punchline. Once, for a laugh, he grabbed a pair of scissors and cut my tie in half. I was in shock while he howled with laughter. As grumpy as Jerry could get, he never lost that naughty glint.

Apart from the gift of his time, the many hours of interviews and the scores of off-guard photographs he allowed me to take of him relaxing and horsing around, the greatest gift Jerry gave me was the feeling of being special.

After each concert performance Jerry would hold court in his dressing room, sitting with a drink while issuing “hellos” and “thanks for coming” to a slowly diminishing queue of people that stretched out the door and down the hall.

Invited to see Jerry after a show, I was told adamantly to stay at the end of the queue. This, I was quickly informed, was at Jerry’s request, and was considered an honour. Being the last in line meant being the person he wanted to speak to the most. It was such a humbling thing to be told that I shuddered.

More so was to be sitting at an outer table at a major fundraiser attended by thousands of people and being told by one of Jerry’s people that he insisted that I come and sit next to him. But it’s no breeze sitting right next to the centre of attention. The rest of the night was spent leaning severely to one side, straining to stay out of the frame of several hundred photos.

To say I’m thankful to have gotten to know Jerry Lewis at such close quarters is a huge understatement. To be a tiny footnote to such a large life is an honour that goes far beyond what I deserve.

And knowing Jerry as I did, he would wholeheartedly agree.

Then he’d cut off my tie.